How Do I Learn To Live With Bipolar? Practical Steps For Individuals And Families

What is bipolar?

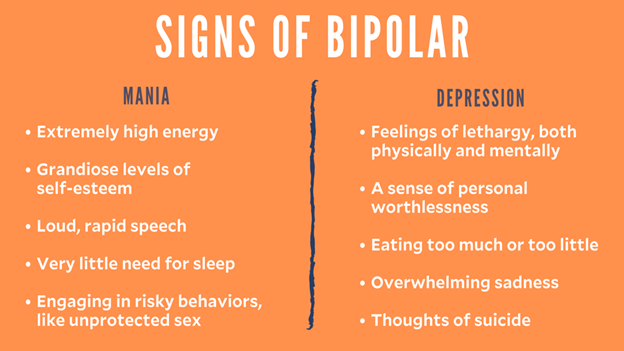

Bipolar is an umbrella term to describe a group of mental health conditions that cause extreme fluctuations in a person’s mood, energy, and ability to function. If you have bipolar disorder, your mood is likely to go through extreme highs (known as mania or hypomania) and lows (known as depression). However, what you experience during each mood, and how quickly or slowly you move between high and low moods, is different for everyone.

World Bipolar Day is an international initiative to stop the stigma attached to bipolar and acts as a celebration of recovery. Bipolar Australia is the peak body supporting Bipolar Disorder in Australia. Bipolar impacts 1 in 50 Australians.

There are different types of bipolar:

Bipolar I disorder

Usually people experience extreme highs (mania) that may be long-lasting, plus depressive episodes, and possibly psychotic episodes.

Bipolar II disorder

Usually experience highs that are less extreme than mania (called hypomania) and only last for a few hours or days. They also have depressive episodes. Between extreme moods, they might have times when their mood is relatively normal.

Cyclothymic disorder

Is a cyclic disorder that causes brief episodes of hypomania and depression. A milder form of bipolar in which moods are not as extreme

What is mania and hypomania?

Mania and hypomania are periods of over-active and excited behaviour that can have a significant impact on your day-to-day life

Duration: In mania, an elevated or irritable mood lasts at least one week. In hypomania, symptoms last for at least 4 days.

Intensity: In mania, symptoms are severe, and in hypomania, they are mild to moderate.

Functional Impairment: In mania, critical life activities such as work and social relationships are impaired. In hypomania, there is generally no functional impairment.

Common early warning signs for hypomania and mania:

- Not sleeping (the most commonly experienced sign)

- Agitation, irritability, emotional intensity

- Energised with ideas, plans, motivation for schemes

- Intense expression laden behaviour with implied extra meaning

- Inability to concentrate

- Rapid thoughts and speech

- Spending money more than usual

- Increased sexual drive, flirtatiousness

- Increasing incidence of paranoid thoughts

- Neglecting to eat, losing track of time

- Reading extra symbolism into words, events, patterns (seeing ‘codes’)

- Increased use of telephone or writing – making contact with many people

- Insistent and persuasive

- Increased intake – or binges – of alcohol and/or drugs

- Arguments with friends or family

- Increased ‘driven’ activity without stopping to eat, drink or sleep

- Increased interest in religious/spiritual ideas or themes

- Taking on more work or working to extremes in hours or projects.

What is depression?

Depression is a mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest.

Duration: Depressive episodes usually last at least two weeks and can last up to around six months or longer.

Intensity: Depression symptoms are classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Functional Impairment: In depression, multiple domains of functioning are typically impaired, including the ability to perform activities of daily living, the ability to form and maintain interpersonal relationships, and work capacity/productivity.

Common early warning signs of bipolar depression:

- Change in sleep patterns – insomnia, or excessive sleeping

- Fatigue

- Staying up late to watch tv or work on projects

- Increased irritability

- Loss of concentration

- Lack of motivation

- Withdrawal – avoiding social contact, not answering phone, cancelling social activities

- Change in eating habits – loss of appetite, or overeating

- Reduced libido

- Increased anxiety and feelings of worthlessness

- Loss of interest in leisure activities and hobbies

- Listening to sad/nostalgic music

- Taking sick days

- Procrastinating and putting off responsibilities

- Bursting into tears for no apparent reason

- Thoughts of suicide.

What can I do to help myself?

If you’re diagnosed with bipolar disorder, it’s really important to work with a mental health professional rather than try to manage the condition on your own. However, research has shown that self-help strategies that are planned with your mental health practitioner can make a huge difference in managing your bipolar disorder:

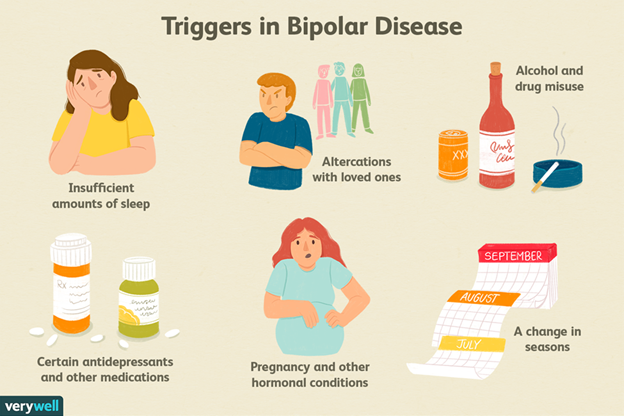

- Monitor your mood. Keep track of your mood daily, including factors such as sleep, medication and events that may influence mood. Use a chart or app to help.

- Establish routines that ensure a regular sleep-wake schedule. Lack of quality sleep is related to mood instability and is often a warning sign of an impending mood episode.

- Limit stress. Where possible, limit stressors in your life and don’t take on too many commitments. This might mean taking one less subject for a semester or working shorter hours.

- Take your time in making decisions. Or ask others such as a trusted family member or friend to help you make decisions if you’re feeling impulsive.

- Build a good support network. Family and friends can help you manage your day-to-day symptoms by giving an outsider’s perspective on your mood. They can also be there when you need to talk about your more difficult moments.

- Join a support group. It can be really reassuring to hear from people who are going through similar experiences. Support groups can offer great advice and comfort.

- Even a relaxing 30-minute walk or 1 to 5 minutes of intensive exercise a few times a week can help health and mood.

- Take time to relax. Relaxation is effective in reducing stress.

- Avoid alcohol and recreational drugs as they may interfere with medications and/or disrupt mood regulation. Talk to your psychiatrist or GP.

- Take your medications as prescribed, even when you’re feeling well, and consult your doctor before making any medication changes.

- Make a wellbeing plan. Keep a record of your plans for how to manage sleep and routines, how to manage highs and lows, and details of contacts if you need help. Make this plan with your mental health professional and give a copy to family and friends.

- Create a safety plan. Prepare how to manage low moods and suicidal thoughts.

How Can I help someone with Bipolar?

- Get educated. The more you know about bipolar disorder, the more you’ll be able to help your loved one. For instance, understanding the symptoms of manic and depressive episodes can help you react appropriately during severe mood changes. Keep in mind that people with bipolar may feel triggered when people label them with their diagnosis. So be mindful of the language used in communication about their illness.

- You don’t always need to provide answers or advice to be helpful. In fact, simply being a good listener is one of the best things you can do for someone with bipolar disorder.

- Be compassionate. For people with bipolar disorder, it can sometimes feel like the whole world is against them. Avoid criticism, blame, judgement and demands. Assuring the person that you’re on their side can help them feel more stable.

- Make a plan. Bipolar disorder can be unpredictable. Establish expectations and responses. It’s important to have an emergency plan in place if you need to use it during severe mood episodes. This plan should include what to do if the person feels suicidal during a depressive episode, or if the person gets out of control during a manic episode.

- Support, don’t push. Become a problem solver. When conflict arises, approach the issue as a mutual problem to be solved together instead of as a disagreement in which one person is right and the other is wrong. However, you need to know when to step back and let a medical or mental health professional intervene.

- Take care of yourself. While you’re caring for someone with bipolar disorder, it can be easy to forget to care for yourself. But before you help someone, you need to make sure you have the time and emotional capability to do so.

- Be patient and stay optimistic. One of the burdens that your loved one with bipolar carries is seeing how miserable it makes you. Feeling sorry for yourself is natural and understandable, but try as much as possible to focus on more pleasant aspects of your life, such as friends, hobbies, and managing your own well-being.

Sources:

https://au.reachout.com/articles/self-management-for-bipolar-disorder

https://www.healthline.com/health/bipolar-disorder/caregiver-support

Hilty, D. M., Leamon, M. H., Lim, R. F., Kelly, R. H., & Hales, R. E. (2006). A review of bipolar disorder in adults. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)), 3(9), 43–55.

Rowland, T. A., & Marwaha, S. (2018). Epidemiology and risk factors for bipolar disorder. Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology, 8(9), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125318769235

Vázquez, G. H., Kapczinski, F., Magalhaes, P. V., Córdoba, R., Lopez Jaramillo, C., Rosa, A. R., Sanchez de Carmona, M., Tohen, M., & Ibero-American Network on Bipolar Disorders group (2011). Stigma and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 130(1-2), 323–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.012